For the most part, my students put up with poetry. Many of them don’t really like it. They find it difficult and it makes them feel dumb. And most of the common strategies that we use, like “SOAPS,” give them too much to manage and make them feel like poetry is too much trouble. Students need a better way to get into a poem and really understand it that doesn’t involve figuring out rhyme schemes and picking apart figurative language, at least not at first.

I find with my my students that if they can answer the following two questions, everything else falls into place a lot easier. The questions are:

What happened?

and:

How does the speaker feel about it?

The first question is surprisingly difficult for students to answer. Many of my students don’t consider a poem to have a “plot” or an “event” that takes place, but the vast majority of poems do. In “The Road Not Taken” a man takes a walk in the woods and chooses between two paths. In “Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer’s Day” the speaker does exactly that. In “Cross,” by Langston Hughes, the speaker is the child of a white father and an African-American mother. And so on.

I like to have my students summarize what happens in a poem in one or two sentences. Many of my students need some practice summarizing, and this gives them the opportunity to have a clear idea of what takes place. Also, when they write about poetry it’s important for them to start any discussion off with a concise description of what the poem is about.

The second question, “How does the speaker feel about it?” is a little trickier, but really gets students talking about the poem. For instance, when the speaker of “The Road Not Taken” sighs at the end of the poem, is it a sigh of contentment, or regret? As students think about how the speaker in “Cross” feels about being “neither black or white,” they often get into a conversation about racial identity.

Seemingly simple poems can start meaningful conversations, such as “This Is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams (is he really sorry? Does this poem make up for taking the other person’s breakfast?) and the two questions can help unlock even the trickiest poems, like “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (does making beauty permanent rob it of beauty in the first place?

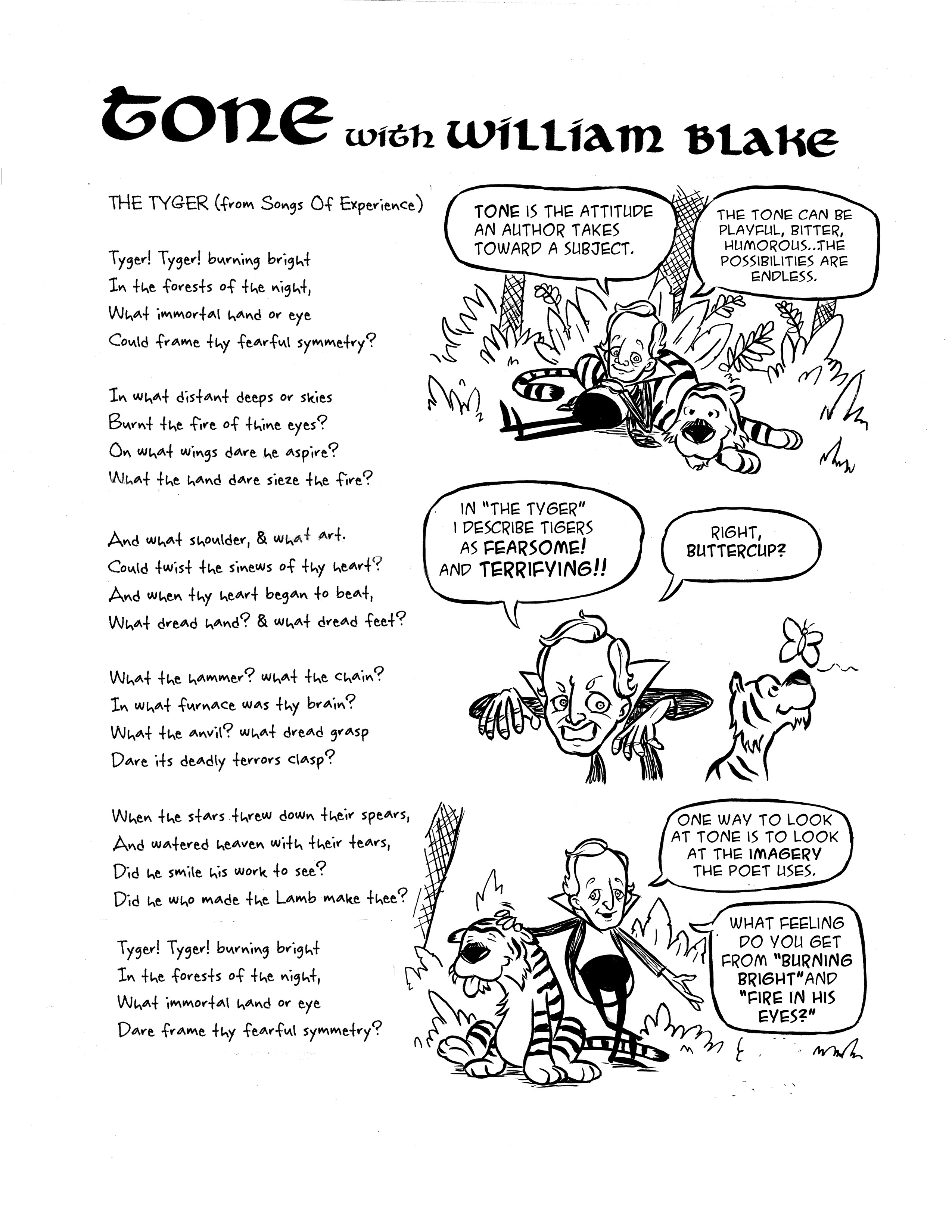

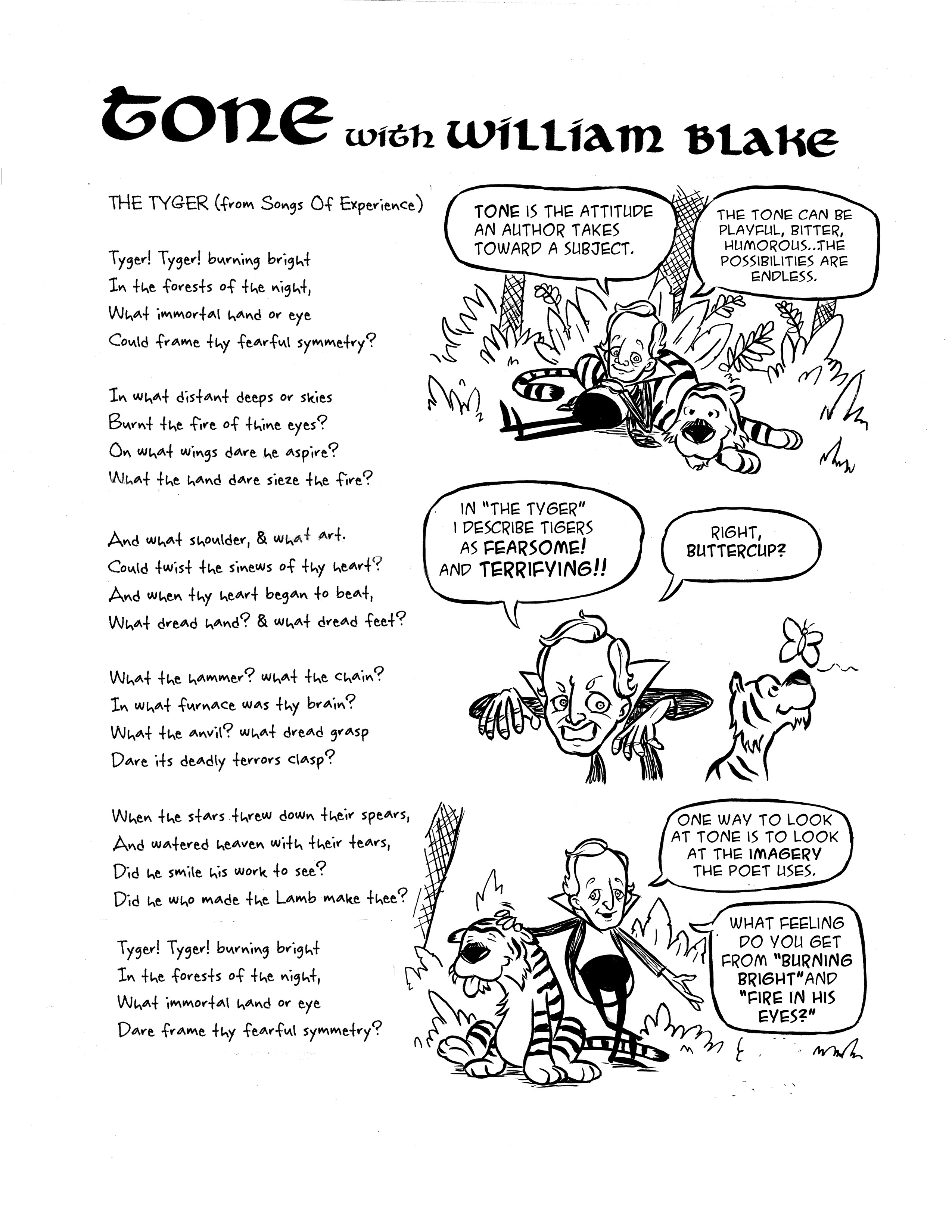

Once students can answer these two questions, they are prepared to look at the imagery and poetic devices used. This is the perfect time to work from the “what” of the poem to the “how” of the poem and look at the figurative language, rhythm, rhymes, and so on.

A perfect poem to introduce these two questions is “To A Daughter Leaving Home,” by Linda Pastan. The answer to “what happened?” is an easy one: the mother describes her daughter riding her bike independently for the first time. So then “how does the speaker feel about it?” Students will point to the fact that the mom is “waiting for the thud” of her daughter falling over, but she doesn’t fall off. Instead, she gets “smaller, more breakable with distance” enjoying here newfound independence. And when you get students to consider the title, they’ll see what the poem is REALLY about (this is a great poem for high school seniors.)

In a larger sense, one of the valuable skills we can teach students is to be able to process what has happened in their lives and determine how they feel about it (and whether their feelings about it are appropriate.) Rarely do we feel one way about something, and poets are no different. Reading poetry can help train students’ emotional intelligence in this way.

Would you like a FREE comic lesson on Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken?” Click the box at the bottom of the post.

Featured Product: