Imagine you’re learning to play tennis. You’ve competed in some matches and haven’t been doing all that well. You go to your coach and ask him what you need to work on. He looks you in the eye and says “Everything.”

Imagine you’re learning to play tennis. You’ve competed in some matches and haven’t been doing all that well. You go to your coach and ask him what you need to work on. He looks you in the eye and says “Everything.”

This isn’t going to be useful information. You may indeed need to work on everything, but where do you start? And what’s most important to work on?

Now imagine that the coach says, “I want you to work on your serve and your footwork.” Now you’ve got two things to work on. It doesn’t mean that the rest of the skills you need to work on aren’t important. It’s just that these focusing on these two skills will give you the best results at this point in your tennis game.

Traditional Rubrics

The problem with traditional rubrics is that they tend to focus on every possible way that students can be assessed. In the pursuit thoroughness, I’ve developed rubrics with fellow teachers that have fifty items on them: 1 point for the heading, 5 points for the topic sentence, and so on. This, we thought, would solve all our problems. Everything you could possibly measure was on there. And of course, when I handed back the papers with those rubrics many students greeted the event with indifference. I’ve always been dismayed when students didn’t look at this rubrics with a furrowed brow, intently taking notes on all the feedback they received to make their work better. But in truth, they didn’t get any feedback that would help them do better the next time.

The problem is that when we grade everything, we tend to grade for ourselves – we want to be able to justify the grade we give if anyone should complain. The problem is that students don’t tend to learn anything from a lot of criteria. And these rubrics don’t save us grading time, which any good rubric should do. It would be far better to just assign a holistic letter grade and move on, answering questions from those few students that want to know why their grade was what it was.

A More Effective Rubric

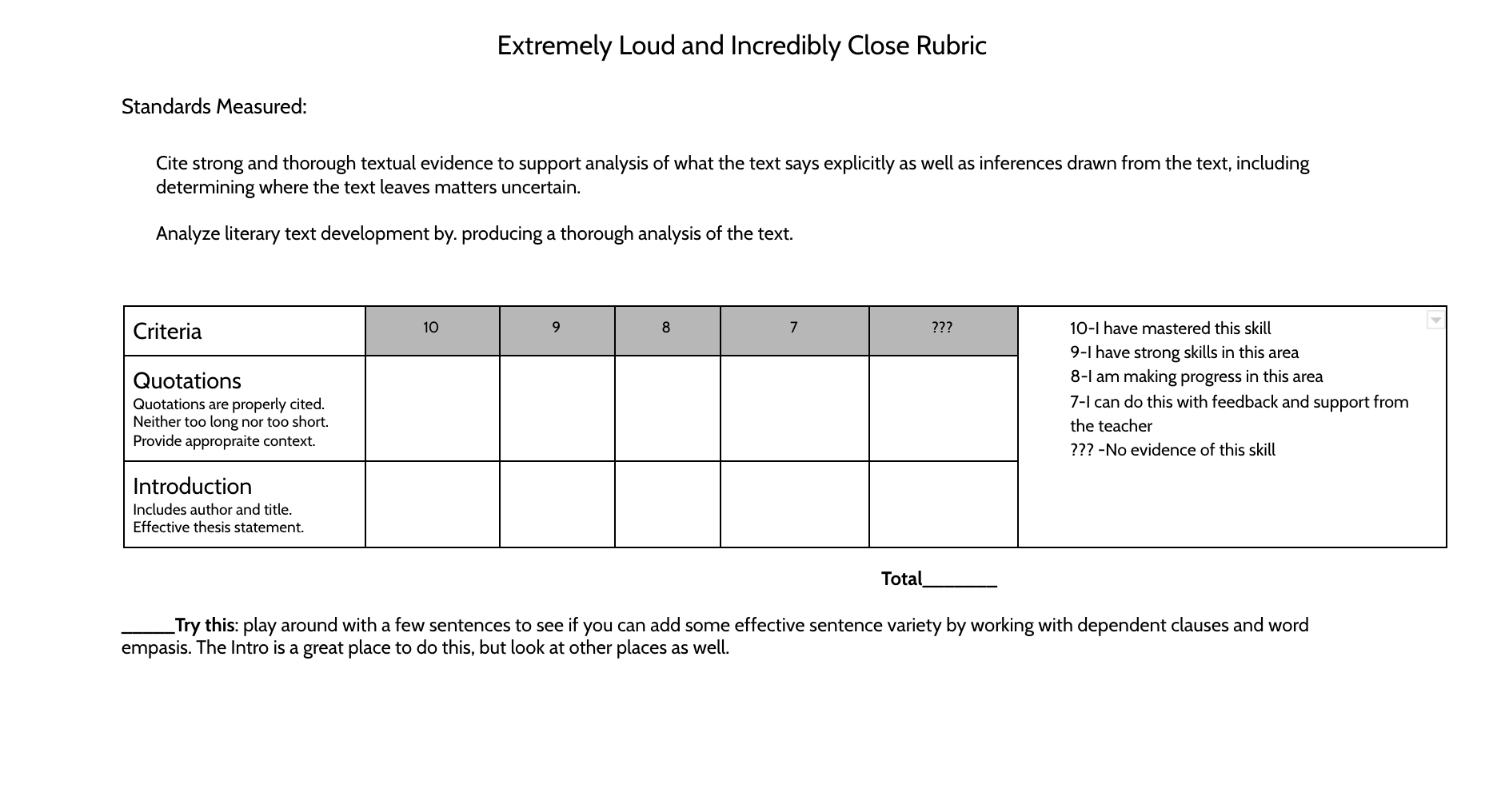

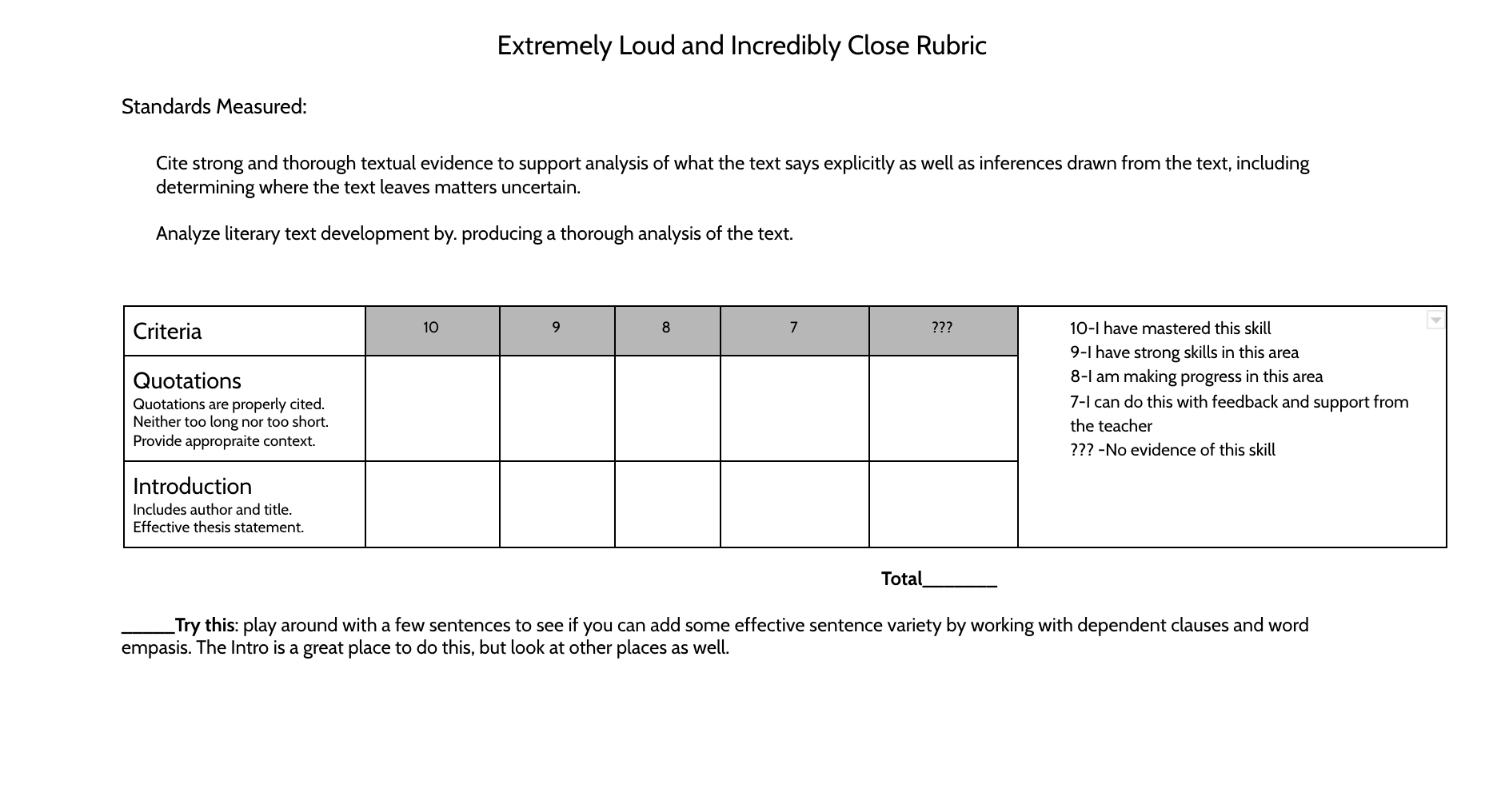

This is why it’s more effective to isolate a few skills instead of focusing on every skill. When I started doing this my grading time went down considerably and my students received targeted meaningful feedback. Here’s the first rubric I used this year with my seniors for an essay over the summer work that was written a few weeks into the school year:

Therefore I’m only looking at two things, not several. Although I might comment on some other things, the trick is you have to resist the temptation to mark everything else that might be wrong that you aren’t assessing on the rubric. It’s hard for me to leave grammatical mistakes alone, but that’s the only way that you’ll save time.

By using this rubric I was able to grade three classes of essays quickly and give timely feedback. Students were then able to use that targeted feedback to do better on their next essay.

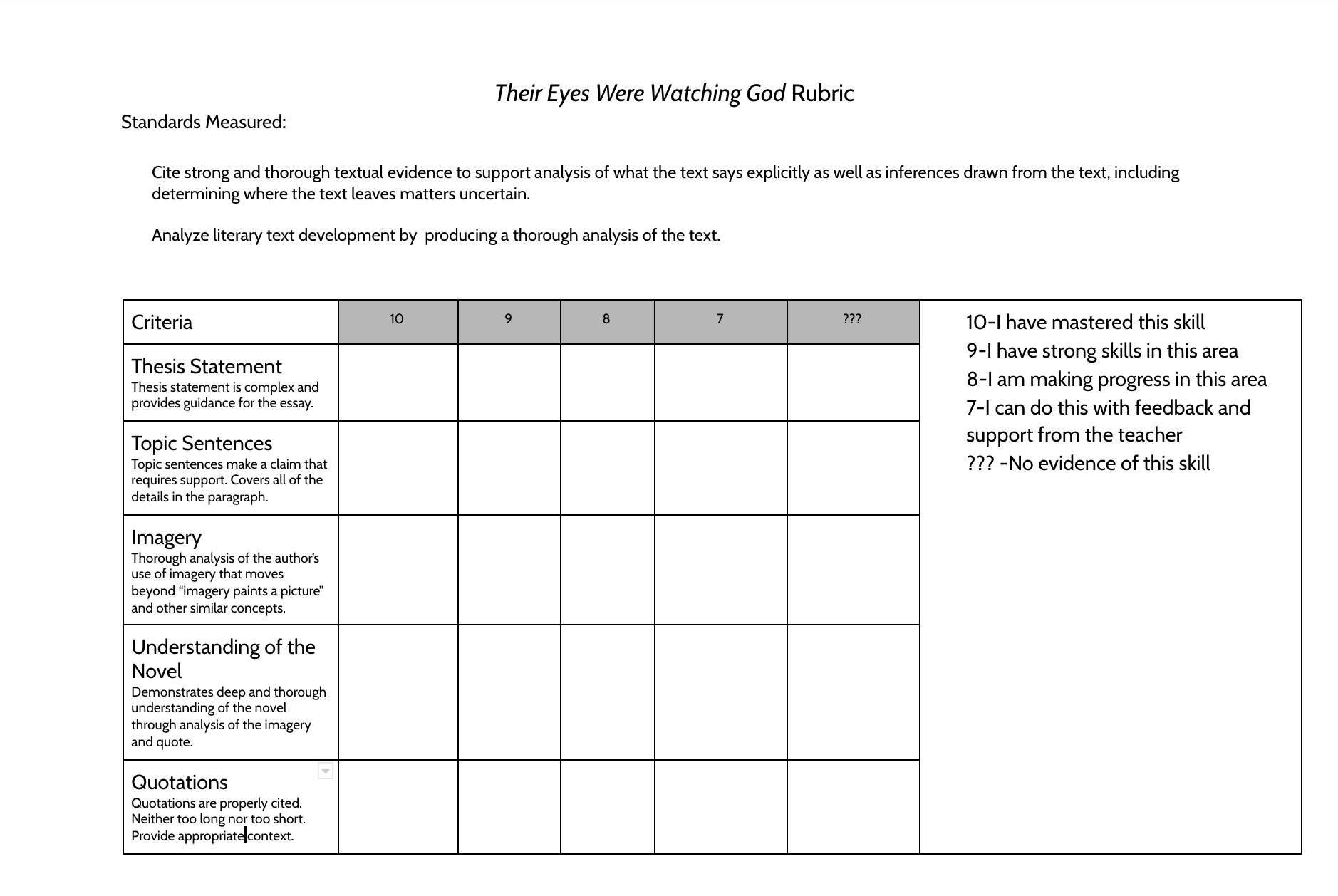

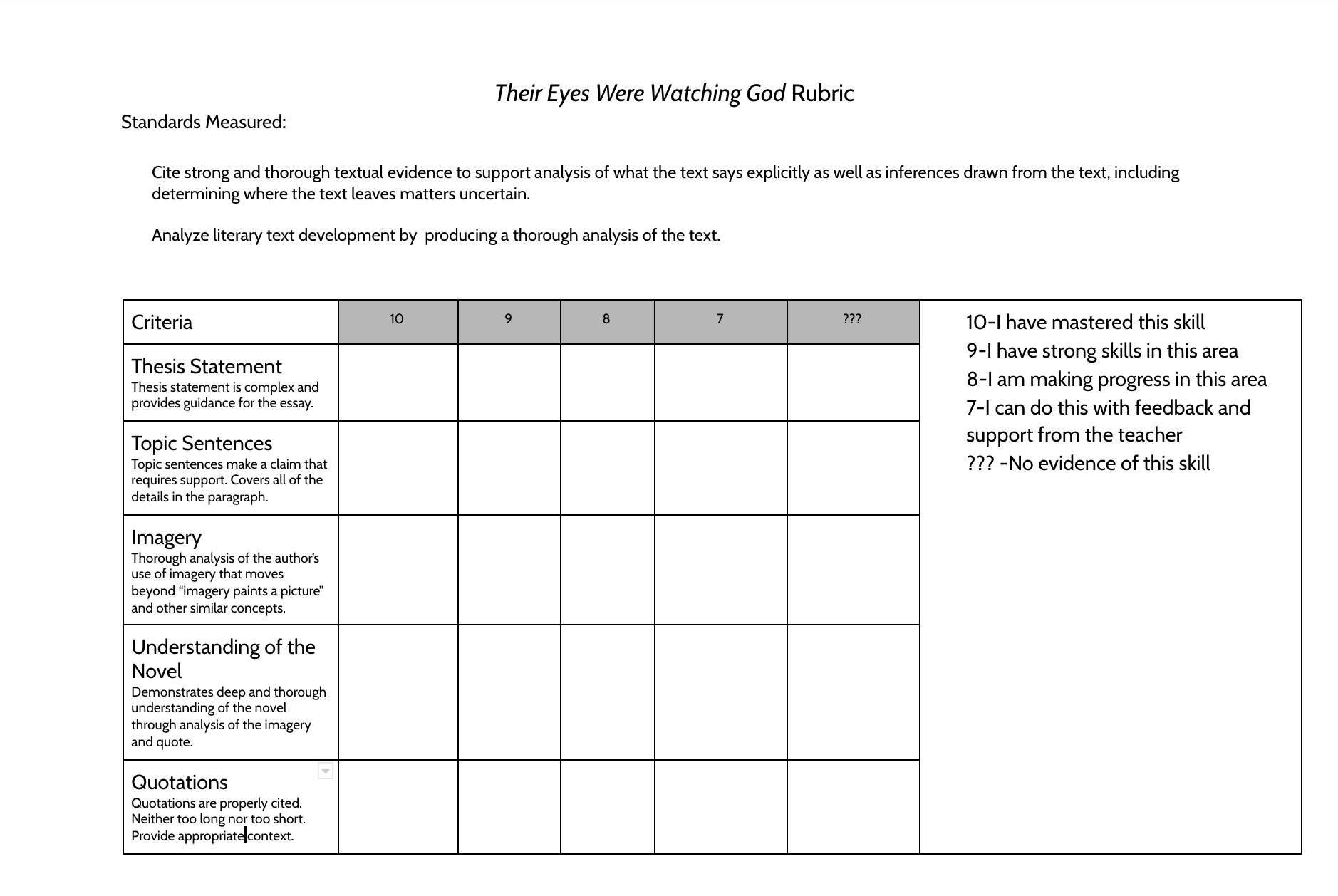

Here’s another example of a rubric that has more criteria:

Same standards, but now I’m looking at different things. I’m only looking at the thesis statement, not the introduction. Quotations remain on there as something we want to continually practice. Topic sentences are measured, but organization isn’t. This is still a more manageable rubric that those I’ve used in the past, and provides for quick, effective grading.

A quick note on mastery

I know some teachers believe that once you’ve mastered a skill, you don’t need to be assessed on it. While this works for some subjects, I tend to disagree with this method in language arts. For one thing, if students have mastered a skill, I want them to continue to be working at that level of achievement, which takes constant reinforcement and practice. To go back to my tennis analogy, if you win Wimbledon you don’t stop playing. You try to win it every year. I want students to demonstrate mastery over the course of the school year and not just one time.

A Final Word

A knew a college professor that had done some research on grading. He found that the most effective number of comments on a paper was three comments. Any more than that and you are overwhelming students with feedback. While I still add more comments that this (I’m still in the mindset that more comments mean I’m doing my job) it’s easy to see that if you had three really good comments you’d be able to give students great feedback to work from. We want to eliminate those parts of grading essays that don’t lead to improvement.

Learning should be fun! Check out my Teachers Pay Teachers store for fun resources like the ones you see below.